The Ship of Lunatics, Davor Mezak, Danko Friščić, video installation, MSU, No galerija, 2014

Award of the HDLU and the city assembly of the city of Zagreb for the best exhibition in 2014.

Historically, it's established that medieval cities would load their madmen onto a ship and send them off to other cities, making every effort to remove them from the community at any cost. Without institutions for the mentally ill and empathy towards those who couldn't fit into society, authorities shifted the problem onto someone else. Today, the phenomenon of the "ship of lunatics " has become a metaphor for dysfunctional groups, often used satirically to critique the powerful but incompetent.

Watch video on the links:

Video I: The Ship of Lunatics, MSU, Nano Gallery, 2014

Video II: The Ship of Lunatics, MSU, Nano Gallery, 2014

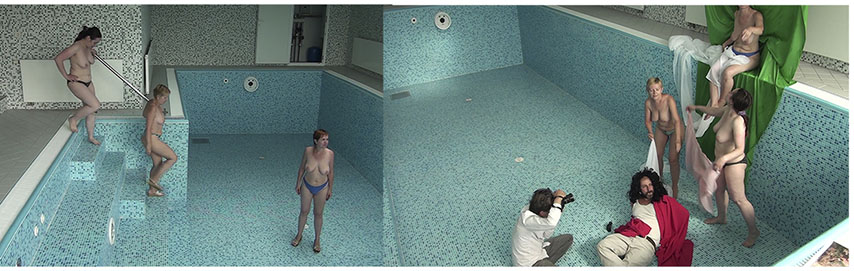

Here, we use it doubly, as self-irony and a perspective on the personal destinies of artists, but also as a metaphor that can describe the Croatian reality. The exhibition "Ship of Lunatics" by the Mezak/Friščić duo is a trilogy consisting of the works "Medusa's Raft," "Gundulić's Dream," and "The Godfather," created over several years, in which the artists confirm their position as a kind of "outcasts" from the mainstream currents of Croatian contemporary art. Outside the dominant artistic currents marked by practices based on neo-conceptual engagement and questioning of social reality on one side, or various appeals of painterly academies on the other, they found themselves in a more open (according to Baudrillard, meaningless, empty but valuable for exploration) space of postmodern citationism, in the aesthetics of the ugly, kitsch, and trash, relying on the cultural and anthropological sediment of the history and culture of the Western civilization circle. Already in 2002, they multimedia reinterpreted Rembrandt's painting "The Anatomy Lesson," and in 2003, El Greco's "The Burial of the Count of Orgaz," thereby early announcing a propensity for the reenactment process, the reenactment of some paradigmatic themes from the history of societies and the history of art and culture. In addition to artistic, such scenic performances, recently performed according to Géricault's painting "The Raft of the Medusa," Bukovac's "Gundulić's Dream," or Coppola's film "The Godfather," have a dimension of a "time machine" that metonymically explains the reality in which we find ourselves. This "revival" of important themes by Mezak/Friščić isn't done "from above" by lecturing on possible solutions. Quite the opposite, their process equalizes themselves and others, where their "self" is merged with others. The artists seek gallery presentation through the medium of photography and video, in an environment made up of ready-made recycled objects, materials, and things that remind the viewer of what they've seen and known, making the main theme more familiar. Actions are regularly endeavors that involve a well-thought-out scenario that usually turns into a chaotic happening from the beginning, with plenty of room for participation and collective reshaping of the original idea. The artists do not make hierarchical or professional distinctions in the assigned tasks between actors, so everyone, literally everyone present, including cameramen and photographers documenting the action, becomes its means but also content. In fact, almost everyone participating in these actions is filmed, and then this material is transformed into a presentational, exhibition form in post-production. The "notes" in the form of multiple video installations with projections and screen displays or city light photographs are very important to the artists because they testify to the fact that it is about a spontaneous, unscripted, sincere transformation of a "serious" theme into a ludic and anarchic phantasm in which everything and everyone is parodied, where roles and functions easily change, and personal and general, history and present, ecology and economy, brutality and love, eros and thanatos, reality and dreams intertwine. The famous (pre)romantic painting "The Raft of the Medusa" by Théodore Géricault from 1819, created in response to the disappointment with the achievements of the French Revolution, depicting the real tragic event of abandoned shipwreck survivors and their undignified fate, served as a motif for the artists to depict the drowning of our civic dignity in the "ocean" of garbage at the Zagreb city landfill Jakuševac. The artists invited a group of acquaintances and artists to join them in their intention to recreate the motif from this historical painting at the landfill. And although the group had a Monty Python-esque good time, the results are burlesque, tragicomic, but powerful and frightening images that iconoclastically deconstruct any idea of the high achievements of global civilization, and on a local level criticize the principles of neoliberal economics that dissolve collectivity and its political nature and turn it into a pathetic crowd of oddballs, just as it happened to the shipwreck survivors of the frigate Medusa who went through the hell of death, disease, rebellion, hunger, and cannibalism, only to later become a nuisance to state authority. The dreams and fantasies that the painter Vlaho Bukovac develops in his allegorical paintings, using the meaning of the character and work of Ivan Gundulić, in spectacular compositions like "Croatian Revival," "Gundulić's Dream," or "The Development of Croatian Culture," from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, are apotheoses of Croatian culture, its history, and contemporaneity. Mezak and Friščić found it sufficient that Bukovac, in all three paintings, especially in "The Dream," played with a situation that indicates eroticism and fits it into the scene of apotheosis. Gundulić in the Dream dreams of Osman, the identification epic of Croatian literature but also of libertarian political ideas, while Bukovac positions him to "manly," completely relaxed and lasciviously, from the edge of the grove, observing semi-naked nymphs (actually Ottoman female warriors) frolicking in the water and mist in the central part of the painting. What does Gundulić actually see, which is not visible in Bukovac's painting? The artists set up their happening in the pool of a Zagreb tycoon's villa with the intention of referencing the composition of the painting and the state of the dream as defined by Sigmund Freud, as a "structure of inherently incomplete imagining and conjecture." Therefore, it's not surprising that there is no water in the pool, that both artists have taken on the "role" of Gundulić, around whom semi-naked women dance, models from the Academy of Fine Arts, grotesque compared to the nymphs from the famous painting. Moreover, one of Bukovac's ideas in Gundulić's Dream, the one about erasing the boundaries between body and spirit, is stripped down to a naturalistic depiction in which only the carnality of naked bodies remains, but precisely because of that, we can peek beneath the skin and confirm their vitality. Isn't that exactly what Gundulić would want to "see" from Bukovac's painting? When Francis Ford Coppola's film "The Godfather" was shown in 1972, with the iconic scene in which Hollywood producer Jack Woltz wakes up in the morning lying in blood and screams in terror as he discovers under the covers the severed horse head of his prized pet, the reactions were shock and disbelief. Namely, it was indeed a real horse head, as testified by the screams of the actors who weren't told that after rehearsing with a fake head, a real one would be used during filming. His screams in the film were not acted. Mezak and Friščić approached the video "The Godfather" from a different direction. They filmed the process of killing a horse in a local slaughterhouse as if it were a making-of of the film "The Godfather." And in this case, the scenes are authentic, and this horse, like the one from "The Godfather," was intended for further sale and was not killed for filming purposes. The brutality of these scenes, the cinematic scenes of a mafia act of extortion and sending a message to the disobedient producer, as well as the process of killing horses from Mezak/Friščić's video, do not differ. A fact that helps us accept the shocking naturalistic images more easily is the thought that in both cases, there is manipulation of reality. In both cases, reality is mediated, through film or video image, and in both cases, it has a metonymic character. And Coppola's boldness, which Mezak and Friščić recreated, leaves open and undefined boundaries of the field of action of art on the viewer in the process of confronting reality and imagination.

Tihomir Milovac